Issue Framing

|

| Framing Public Life: Perspectives on Media and Our Understanding of the Social World |

|

| Bullying, Cyberbullying and Student Well-Being in Schools: Comparing European, Australian and Indian Perspectives |

It is probably quite

instinctive to consider how different problems in the world compete for

attention from policymakers. There are so many problems to address, which ones

are going to get priority? On the other hand, consider how different framings

or definitions of problems are also competing for attention. Statements about a

set of social conditions defining it as a problem represent interpretations and

framing from a wide array of possibilities. It involves various potential

framings or definitions contend for attention on policy agendas. Perhaps you’re

wondering if data and scientific evidence definitively reveal the correct

problem definition. Indeed, an objective framing of social problem should

involve good data, information and evidence. However, it’s also accurate that

in defining a set of conditions as a problem, it also entails defining those

conditions as bad in some manner. Perhaps the conditions are bad because they

are causing harm to people. Individuals or societies could improve. People are facing

unjust or unequal treatment. People or communities are being treated unfairly,

et cetera. The point here is that all problem definitions for public policy

encompass some normative element. This means they incorporate some value

statement or moral reframing, incorporating concepts of what’s good and bad for

people or communities, and also what’s good or bad for the government to do and

what should the government do or refrain from doing through policy? To recap,

getting issues or problems on public policy agendas, there’s competition among

a variety of problems. These problems compete for limited space on the agendas

of the media, advocacy organizations, political parties and the government.

They must be part of these agendas before there will be a policy debate in

response. The important point is that before these problems be part agendas,

there’s also a process by which specific conditions in society have been

labeled, constructed or framed as a problem. These different framings or

definitions themselves compete for our attention to not only get on policy

agendas, but in the end, get a public policy response to the problem as it has

been defined.

Let’s delve into the

intricate issue of firearm violence in the US, the United States has a

significantly higher number of guns per capita compared to other countries and

higher rate of violence related to firearms compared to other countries. This

includes violence in the form of homicide, mass shootings and suicide. One

framing of the problem of the firearm violence in the United States is that the

ease of gun carrying and ownership. There is an excessive number of firearms in

circulation, with easy access to purchase, possess and carry them in public

spaces. This indicates an overabundance of firearms present in both public and

private spaces. In this framing, it has also suggested that this extensive

availability to firearms creates an environment in which firearms have become a

leading contributor to mortality, injury and suicide. However, other framings

of the problem of firearm violence in the United State propose that the problem

is not guns, the problem is people. The problem is that there are some

individuals with violent tendencies who choose to employs guns in their acts of

violence. Some people who are criminals, who are evil or mentally ill, misuse

firearms, making it challenging to prevent them from carrying out their violent

intentions. Also, in some related framing of the problem, the idea is that by

having more people with guns in public spaces they can be prepared to intervene

in situations where violent individuals are attempting to harm others. This

perspective suggests that the problem of firearm violence, It is

considered by many that more regulation and restrictions fail to address the

mental health, public health and safety problems in American society. Policy

proposals to limit the access to firearms will not effectively address that

problem of bad people or mentally ill people who misuse firearms. Lastly, the

right to bear arms is enshrined in the US Constitution. Many individuals

believed that the enshrinement of a right takes precedence over all other

societal concerns, there are different perspectives on what public policy

should and should not do to address the issue of firearm violence. Additionally,

the issue of firearm violence in the US is multifaceted, which cannot be

reduced to just two framings of the problem. Diverse priorities and values that

are applied on competing definitions of the problem. Moreover, it is to

acknowledge that not only do social problems compete for attention on policy

agendas, but also the various ways in which they are defined and framed as the

problem also compete for attention. Please keep in mind that social problem

framing is a collective or group

political process that involves both data and evidence together with values.

Framing and Policy Making

https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/article/framing-and-policy-making/

Policy Target Groups:

Benefits Vs Burdens

|

| Burden or Benefit?: Imperial Benevolence and Its Legacies |

Anne

Schneider and Helen Ingram's convergence theory suggests that the convergence

of political power and social framing of potential policy target

groups creates four distinct groups, with different policy benefits versus

burdens. This model further predict the types of benefits and burdens that each

of the four groups will likely face in public policies. Let’s take a closer

look at each group.

- Groups that

are positively constructed in society and have significant political power are

categorized as advantaged. This groups having political power, means being able

to influence how policy is designed and whether it will result in burdens,

benefits or even face the possibility of not being approved. For the advantaged

group or those with a positive social framing and political power, the model

predicts that public policy is most likely to bring more benefits than burdens.

The data suggests that the balance between burdens and benefits is weighted

towards benefits. Some examples of advantaged groups include the elderly,

veterans, scientists and science organizations and some businesses, especially

those seen as providing a social benefit.

Groups: Process and Practice - Groups that are negatively constructed in society but have political power are referred to as "contenders". The model predicts that contenders, with their negative social framing but significant political power, will experience benefits but they are often hidden, and fewer burdens than other groups. Some examples in this group are pharmaceutical companies, insurance companies, wealthy elites and the National Rifle Association and gun manufacturers.

- Groups that are positively constructed in society yet have no political power in turn, are called “dependence”. For dependence, groups with a positive social framing but limited political power, are likely to experience both burdens and benefits but the benefits potentially symbolic, weak or hidden. Some examples of groups in this category are children and people in the disability community.

- Then finally, groups that are negatively constructed and don’t have any political power are referred to as deviants. For deviant, characterized by low political power and negatively constructed in society, the model forecasts that public policy will predominantly impose burdens, with only a few, if any, weak in benefits. Additionally, if policy does bring benefits to groups in this category, it often involves significant burdens, including administrative burdens, work requirements for public assistance or other kinds of burdens. Some examples of groups in this groups are people with drug addiction, sex workers, people who have engaged in criminal behavior, and people living in poverty or require public assistance.

In summary,

the key points from the lessons. First, the social problems that a public

policy aims to address has been constructed, framed and defined through social

and political processes. In addition, every group that receives attention

whether positively or negatively through public policy has also been framed or

defined through social and political processes. As a result, the ways in which

social problems and policy target groups are framed plays a crucial role in

shaping the policy options that are under consideration, prioritized and

implemented. Everything about this is value laden, refer to something that is

heavily influenced or characterized

by specific values, beliefs or principles and value – driven, refer to

something that is guided or motivated

by certain values or principles. Values are the foundation of this process and

drive every aspect of it.

Issue

Framing: Perspective from Advocates

Mastering the art of framing is a key strategy for enhancing the effectiveness of a social movement. Framing is a tool that helps people see issues from a different angle and discuss them in new ways. This is the process of communicating ideas and concepts through specific language, imagery, and associations that shape our understanding. Our perspectives on morality and emotions. For instance, in the United States, before 2003, the responsibility for providing care and shelter to unaccompanied migrant children was entrusted to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which also handled law enforcement duties. As policemen, prosecutors, and parents, they lacked the necessary skills and expertise to provide adequate care for children. In 2003, Congress transferred the responsibility for caring for unaccompanied migrant children from the Immigration and Naturalization Service to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). The Office of Refugee Resettlement is more equipped to provide care and support to children, free from the conflicts of interest that the Immigration and Naturalization Service faced. The Office of Refugee Resettlement is more equipped to prioritize the well-being and best interests of children. The Office of Refugee Resettlement is free from the conflicts of interest that the Immigration and Naturalization Service had when it came to shifting the care and custody of children. We had to reframe how children are seen and treated. This required distinguishing between children's and

|

| Reframing the Social: Emergentist Systemism and Social Theory |

Systemic Inequality: Displacement, Exclusion, and Segregation

Reading:

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/systemic-inequality-displacement-exclusion-segregation/

Public Policy and Social Inequality

The Public Good: Equity vs. Equality

In public administration, the pillar of equity involves applying an equity lens to analyze and address issues and problems. An equity lens is a framework for examining, including with data, social problem definitions and framing, public policy agendas, prospective policy solutions and the administration of governmental agencies, programs and public goods using a perspective that takes into account the effects of systemic bias, discrimination and oppression on marginalized groups related to gender or sex, ethnicity, or culture, race, religion, age, geographic area or any other social factors that are involved in creating unfair differences in access to resources, opportunities and the protections of rights.

|

| Inequality and Equity: Economics of Greed, Politics of Envy, Ethics of Equality |

Second, Disparities. Our differences in which various sub-populations or groups differ from each other. But these differences are understood to be driven by things outside of the individuals involved in their own personal preferences. Disparities specifically refer to measurable differences in the distribution of resources or services that are associated with significant social, economic, or health impacts. Disparities often involve unequal treatment or unequal access to resources, which can lead to unequal outcomes. For example, disparities in healthcare might manifest as differences in health outcomes or access to healthcare services based on race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

In the context of public goods, understanding and addressing these differences and disparities is crucial for ensuring that resources are distributed fairly and effectively to all members of society. This involves recognizing the inherent differences in people's circumstances and addressing these differences to achieve more equal outcomes, rather than just equal access. Disparities or differences that exist because of differences in resources, opportunities, discrimination, etc. Not because of personal preferences or choices.

Inequalities are differences in outcomes that are deemed as unfair and unjust because they are unequal or not the same. Inequalities are differences in both inputs and outcomes that are deemed as unfair or unjust because of differential access to the resources, opportunities, environments and treatment that’s required for equality.

Let’s think about equality versus equity instead of inequality and inequity. Equality is when each individual, group or community has the same resources, opportunities, treatment and outcomes. Important things that we care about in the public sector are equal or the same. Equity, on the other hand, recognizes that individuals, groups and communities have different circumstances and in turn allocates or uphold the resources, opportunities and experiences given to each that are needed to achieve equal outcomes. For example, in relation to health disparities and social justice. Equity recognizes that each person has different circumstances and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome, whereas equality means each individual or group of people is given the same resources or opportunities.

The concept of "public goods" is a crucial aspect of understanding the differences between equity and equality. Public goods are resources or services that are available to all members of a society, such as healthcare, education, or infrastructure. The allocation of these resources is critical in ensuring that they are distributed fairly and effectively to all members of the society. In the context of public goods, equity and equality are distinct principles that guide how these resources are distributed. Equality refers to the distribution of resources in such a way that each individual or group receives the same amount or access, regardless of their individual circumstances or needs. This approach is often based on the idea that everyone should have equal access to the same resources, regardless of their differences. For example, in a healthcare system, equality might be achieved by providing the same level of care to all patients, regardless of their health status or socioeconomic background.On the other hand, Equity is about ensuring that resources are distributed in a way that addresses the differences in needs and circumstances among individuals or groups. This approach recognizes that people have different needs and circumstances that affect their ability to access and utilize resources. For instance, in a healthcare system, equity might be achieved by providing more resources to those who need them most, such as those with lower socioeconomic status or those with chronic health conditions. This approach acknowledges that people have different starting points and that the goal is to level the playing field to ensure equal outcomes, not just equal access.In the context of public goods, equity is often preferred because it acknowledges the inherent differences in people's circumstances and seeks to address these differences to achieve more equal outcomes. This approach is particularly important in addressing health disparities, where people from different backgrounds may face different barriers to accessing healthcare services. By prioritizing equity, public health systems can ensure that resources are distributed in a way that addresses these disparities and promotes better health outcomes for all members of society

Data analysts in the public sector are often asked to explore data for both differences and disparities. This type of exploratory data analysis and data visualization is best conducted as objectively, detailed and clear as possible. The data should provide a comprehensive picture of the magnitude, direction, and temporal changes in these differences and disparities. Once the data is analyzed and presented, the interpretation phase begins, where the distinction between civil rights and human rights becomes crucial in determining whether differences represent inequality or inequity, and whether they are grounded in notions of deservingness and fairness.

Furthermore, to analyze differences from a rights perspective, it is essential to distinguish between civil rights, which are legally enshrined and enforced by governments, and human rights, which are based on universal codes of morals and ethics, encompassing the inherent dignity and worth of all individuals.

In philosophy, there's a fundamental

notion that rights and duties are intertwined. If someone has a right, then

another entity has a corresponding duty to uphold that right. This concept is

particularly relevant when discussing governments and the public sector, where

the duties of a government are limited to upholding civil rights that are

codified through formal policy and laws. However, in public sector data

analysis, the transition from data highlighting differences and disparities to

claims of inequality and inequity can be more complex. But the point here is

that most, not all, but most governments are designed to care about equity and and

data plays a crucial role in this endeavor by illuminating social equity and

inequity issues through meticulous analysis and visualization. It is the data

analysis and data visualization that shine bright lights on social equity and

inequity issues.

Let’s end with a graphic that tries to illustrate the difference between equality, equity and then justice, which includes what governments can do to address inequities.

The first panel of this graphic

depicts three people trying to watch a baseball game from behind a fence and

chose equality. But also the flawed assumption that everyone benefits when

provided the same or equal resources or supports, or gets equal treatment,

which in this case is a box of exact same size to stand on, to see over the fence. This equality and support or

treatment does not create equal outcomes as the shortest person on the right,

still cannot see over the fence to see the game. Again, there’s equality and

support, but an equity in the outcome.

The middle panel shows each person

getting what they need to see the game. The first – person gets nothing because

they can already see the game. The second person gets a box, the height needed

to facilitate seeing over the fence. The third person gets an even taller box

to facilitate their ability to see over the fence. This different or inequality

in treatment is what leads to equity in the end.

However, one more important

point, the last panel shows the three people watching the game with

the wooden fence gone. The barrier that created the different levels

of a problem or different obstacles for different people was actively

removed. Now a chain link fence is now in place that still protects

the crowd, but also allows everyone to see the game. In this analogy,

this removing the structural barrier is referred to as

justice. All people can now achieve the goal of seeing the game

without additional support or accommodation because the root cause of

the inequity was addressed. Again, this is just an analogy to unpack

more the concepts of equality, equity, and then also addressing root

causes of inequity removing structural barriers.

Example:

Digital Equity

The importance of equality and equity in the public sector has been emphasized, along with the vital role of exploratory data analysis and data visualization in uncovering and addressing differences and disparities that governments may label as inequities and in turn devise interventions to address.

|

| Enhancing Digital Equity: Connecting the Digital Underclass |

Moving forward, we will delve into the topic of digital equity, which refers to the conditions necessary for all individuals and communities to have access to the information, technology, and capacity needed for full participation in education, the economy, democracy and all aspects of society, with internet access being a fundamental public good. A public good is a resource that provides a social benefit to society and populations, characterized by non-rivalry, where use by one does not diminish the availability for others, and non-excludability, ensuring equal access for all.

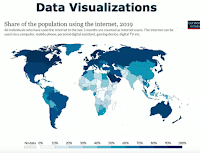

In the context of digital resources, the current state is far from ideal, which is why efforts are focused on implementing measures to achieve digital equity. Key elements of digital equity include affordable and consistent broadband Internet access, access to Internet-connected devices, and access to apps and resources that enhance work, education, and collaboration. Additionally, digital inclusion involves support mechanisms such as tech support, user-experienced support, and broad public education. Data visualization plays a crucial role in understanding levels and trends in digital equity.

In summary, if basic information technology and Internet access are considered public goods, then the government should prioritize achieving equal access and use for all. Data highlighting inequalities in access and use are crucial for informing these efforts, and digital equity involves providing communities and individuals with what they need to bridge the gap towards equality.

Public

Policy and Structural Inequality

|

| Understanding the Dynamics of Global Inequality: Social Exclusion, Power Shift, and Structural Changes |

As an example, this graph demonstrates the persistent gender gaps in wages or pay that are found across a wide range of developed countries. The gender pay gap cannot be attributed to differences in educational background, time, and experience in the labor market or different types of jobs between men and women, as research has consistently shown.

The graph

demonstrates the striking differences in life expectancy between different

racial and ethnic groups in the United States. The data reveals that life

expectancy is decreasing across all racial and ethnic groups in the United

States, but the magnitude of this decline varies significantly, with American

Indians and Alaska Natives experiencing the lowest life expectancy and the

largest decline between 2019 and 2021.

You're already aware that socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, gender, and other social factors all play a significant role in determining outcomes. The key question is, what explains the widespread nature of social inequality? How do we understand this complex issue? First-order explanations attempt to explain the individual factors that contribute to the unequal distribution of outcomes like education, wealth, health, and so on, within society. This is an individual-level explanation that includes factors such as personal endowments, which are the natural talents or abilities that individuals are born with, as economists and researchers like to call these.

However,

it's the innate characteristics that people are born with, such as genetics,

natural talents, abilities, and traits, which are often referred to as gifts of

nature. Other explanations for social inequality emphasize the impact of

individual choices on exploiting opportunities and the willingness to work

hard. Additionally, differences in social outcomes could be a result of the

choices made by families and individuals. Positive outcomes will arise from

making deliberate, well-considered decisions rather than making rash, negative

choices, taking excessive risks, or neglecting the future, et cetera.

Moreover, we need to consider whether these first-order explanations are able to fully account for the social inequality observed in the United States and many other countries. Are opportunities and resources universally accessible and equally distributed among all individuals? Do all people have the same opportunities to make positive choices, utilize resources, and succeed in society? Every social and population science, including economics, sociology, political science, psychology, public health, and demography, has a body of theory and research that emphasizes the need for a multifaceted understanding of social inequality, extending beyond individual-level explanations. We need to move beyond first-order explanations and consider second-order explanations that reveal how persistent racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic differences in social and health outcomes are shaped by differences in exposure to both positive and negative factors. Community-level resources and investments, including environmental factors like air quality, lead pipes, and community cohesion, are essential for promoting the health, well-being, and economic development of local communities.

|

| Embodying Inequality: Epidemiologic Perspectives |

The physical and social environments of communities are critical factors

in determining economic, social, and health outcomes, and are nested within

broader societal systems that are influenced by public policy in both positive

and negative ways. Building on the socio-ecological model, let's explore the

different contexts in which discrimination and differential treatment based on

race and ethnicity can occur. We must acknowledge that racism exists and

operates in distinct ways at each level of the socio-ecological model. At the

highest level of the socio-ecological model, we need to consider how

second-order drivers of inequality, such as systemic biases and structural

inequalities, influence societal systems in often subtle yet profound ways.

Discriminatory or unfair practices can also exist within institutions and

organizations.

When we think of racism and discrimination, we must also consider the

role of interpersonal racism, where individuals reveal their bigotry and bias

through their words and actions. Examples of interpersonal racism include

individuals with power to influence others, such as those who make hiring or

promotion decisions, or those who interact with others in everyday settings

like stores, schools, or restaurants. I believe that when people think about

racism, they often start with interpersonal racism, as it is a level of racism

that is easy to understand and relate to. Moreover, racism and bias can

manifest at all levels of the socio-ecological model, from individual to

societal. Research has found that some people, often starting as children,

internalize the racist and biased messages they receive from others, from

societal institutions, from culture, from individuals and in internalizing

these messages, leading them to feel less deserving, have different abilities,

and have fewer opportunities and resources. Second-order drivers of social

inequality, such as racial inequality, can be internalized by

individuals, influencing their perceptions of their own opportunities,

choices, abilities, and deservingness.

The iceberg

analogy for racism, developed by Professor Gilbert G, highlights the

distinction between the visible, overt expressions of racism and the

often-invisible, systemic and structural factors that contribute to its

persistence. The iceberg's tip is comprised of overt hate crimes, white

supremacist rhetoric and actions, racial jokes, and racial slurs, which are

both morally reprehensible and illegal. Racism, however, is expressed

in society and many other ways that are invisible and below this

tip of the iceberg.

This

includes all of the examples on this slide, including

such things as the legacies of racial residential segregation

on schools and educational experiences, as well as the legacies of segregation

on bank red lining and its impact on the ability of black

people to purchase property, gain wealth, and contribute

to intergenerational wealth and upward

mobility. Additionally, there is a well-documented school-to-prison

pipeline for black males in the United States, which includes

differential punishments by race for the same offense, starting

in school and continuing into the criminal justice system.

Furthermore, there is a great deal of even less visible racism that

operates at these and other levels in society that are way

underneath the surface and much harder to see.

Dr. Paula Braveman is a respected physician and social scientist who has conducted groundbreaking research on the social and economic factors contributing to health disparities, particularly in the context of racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes in the United States and other countries. The disparities in health outcomes are starkly reflected in differences in life

|

| Ehealth Solutions for Healthcare Disparities |

As we delve

deeper into the realm of public policy, it becomes essential to recognize that

these systems are not only created but also maintained and reinforced by a

network of structures that have evolved over time. As we delve deeper into the

realm of public policy, it becomes essential to recognize that these systems

are not only created but also maintained and reinforced by a network of

structures that have evolved over time. Dr. Braveman's analysis focuses on the

structural components or designed elements within systems that create and

perpetuate differential treatment. The research highlights the far-reaching

impact of systemic racism, encompassing both the cultural and social norms that

shape our values and beliefs, as well as the public policies that govern our

society and influence individual experiences. The analysis emphasizes the

crucial role of policy implementation and enforcement in determining the impact

of laws, regulations, administrative rules, and burdens for access to programs

and resources and the ways in which policies are implemented and enforced.

These structures can be viewed as the underlying infrastructure or the foundation that supports and sustains systems, encompassing both public sector systems and those governed by laws, regulations, and policies. Dr. Braveman's explanation may have become intricate, but to simplify the concept, let me provide a concise summary. Public policy serves as the fundamental framework or infrastructure that supports and influences the operation of key societal systems, providing the essential foundation for their development and effectiveness. Public policy serves as the fundamental framework or infrastructure that supports and influences the operation of key societal systems. Public policy can also incorporate biases, differential treatment, and structured chance, which can perpetuate racial and ethnic disparities, and this is what can be defined as structural racism. That’s the bad news. Meanwhile, while public policy can perpetuate racial and ethnic disparities, the positive news is that these policies can be reformed and changed. If there are ways in which laws, regulations, public programs, rules, or other features of our social systems are contributing to these higher levels within society of racism, these can be changed. Public policy is a crucial component in understanding social inequality in our society. public policy plays a crucial role in shaping and perpetuating systemic and institutional racism. This implies that public policies, whether intentional or unintentional, can contribute to the creation and maintenance of racial disparities and inequalities in various aspects of society, such as healthcare, education, housing, and employment. It also serves as a pivotal platform for driving transformation, with the development and implementation of innovative and reformed public policies being essential for achieving social change, particularly related to the core pillar of equity.

The Importance of Equity in Public

Health: Interview with Dr. Joneigh Khaldun

Throughout

this course, we have explored the fundamental principles of public service,

including efficiency, economy, effectiveness, and equity, which serve as the

foundation for delivering high-quality services that benefit the public.

I would like

to catch up the conversation between Professor Paula Lantz and Dr. Joneigh

Khaldun and gain valuable insights about the topic. The conversation between

the two individuals revolves around the concept of equity, specifically in the

context of public policy, public services, and public programs. They discuss

the importance of equity as a core principle and fundamental motivator for

their work, emphasizing that it is critical to everything they do in public

service. They define equity as ensuring that everyone has an equal chance to be

as healthy as possible, regardless of their background, circumstances, or

demographics.They highlight the challenges in addressing equity and inequities,

citing the need to understand root causes, disparate treatment, and disparate

access to resources. They emphasize the role of data in addressing inequities,

noting that it is essential to consider the impact on historically marginalized

communities, including racial, ethnic, and minority groups, as well as those

with different abilities, older individuals, and those living in rural

areas.The conversation also touches on the importance of integrating equity

into all aspects of work, making it a core principle and not just a one-off

initiative. They discuss the challenges of changing how people do their work to

prioritize equity and the need for intentional and inclusive practices.

Additionally, they share examples of successes in communicating data to

policymakers and the importance of understanding the broader goals and

constituents in decision-making processes.

Everyone

deserves equal access to healthcare and wellness opportunities. This policy

imperative recognizes that not all individuals have equal access to resources,

such as healthcare facilities, education, or economic opportunities, which can

impact their ability to maintain good health.

Here are the answers to the questions

posed in the conversation:

- What does equity mean to you in terms of public policy, public services, and public programs? Equity means ensuring that everyone has an equal chance to be as healthy as possible, regardless of their background or circumstances. It recognizes that not everyone has the same resources and that disparities in health outcomes are driven by social inequities.

Evaluating Challenges and Opportunities for

Healthcare ReformHow do you think about allocation of resources, supporting communities?The conversation does not explicitly discuss the allocation of resources or supporting communities. However, it emphasizes the importance of understanding the root causes of inequities and addressing them through intentional and inclusive practices.- How do you engage communities in a genuine way?The conversation highlights the importance of recognizing communities as experts in themselves and engaging them in a genuine way. This involves understanding their needs and perspectives and involving them in the creation of solutions to address inequities.

- What do you see as some of the biggest challenges for the public sector in addressing equity and inequities in all forms?

- The biggest challenges include identifying and addressing root causes of inequities, such as disparate treatment and access to resources. The conversation also emphasizes the need to change how people do their work to prioritize equity and the importance of integrating equity into all aspects of work.

- Can you talk a bit about the powerful role of data in this work?Data play a crucial role in addressing inequities by providing insights into how different communities are impacted and how they can be brought into the creation of solutions. The conversation emphasizes the importance of using data to guide policy development and decision-making.

- Can you talk a bit about some successes you had in communicating to people who control resources or policy decision-makers, communicating data to them in a way?The conversation shares an example of successfully communicating data to policymakers in the context of addressing infant mortality in Detroit. The approach involved presenting data in a way that was easy to understand and actionable, and it led to targeted interventions based on the data.

- Do you have any advice for our learners who are interested in going into data analytics and the public sector, but really do share your core and my core interests in that equity pillar in public service?The conversation advises learners to understand the people and the core work of the organization they are working in, as data is always about the people. It also emphasizes the importance of presenting data in a way that is easy to understand and actionable, and of remembering that data is always about the people and the work.

Discussion

Prompt

The

discussion revolves around various social issues that affect individuals and

communities worldwide. These issues include:

- Healthcare Inequality: The lack of equal access to healthcare services and facilities is a significant problem, leading to health disparities and poor health outcomes. Healthcare workers are leaving the country for better compensation and benefits, further exacerbating the issue.

- Mental Health Stigma: Mental health stigma is a pervasive issue that hinders individuals from seeking support and receiving adequate treatment. It is rooted in societal misconceptions, cultural beliefs, media representations, and inadequate education about mental health. The consequences of stigma include increased suicide rates, reduced treatment adherence, and overall poorer mental health outcomes.

- Homelessness: Homelessness is a significant problem affecting individuals and families from diverse backgrounds. The root causes of homelessness include the scarcity of affordable housing, poverty, mental health challenges, and substance abuse. The consequences of homelessness are far-reaching, including increased vulnerability to violence, health issues, and barriers to employment and education.

- Cyclical Poverty: Despite the emphasis on meritocracy and equal opportunities, significant disparities at birth hinder many from competing with the affluent. The wealthy can access more resources for their children, further skewing the playing field in their favour. The tuition industry has become a lucrative opportunity for affluent families to invest in their children's educational development.

- Rural Poverty: Poverty rates in rural areas are significantly higher than in urban areas. The root causes of this problem include economic decline, inadequate infrastructure, and limited public services. The consequences of rural poverty are far-reaching, resulting in poor health outcomes, lower educational attainment, and economic stagnation.

- Housing Affordability and Accessibility: The persistent issue of housing affordability and accessibility for individuals from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and demographics remains a pressing concern. Structural and systemic barriers, including intergenerational wealth disparities, hinder access to housing for marginalized groups. Housing policies and policies affecting the cost of living can exacerbate the issue.

Policy

Agenda Setting and Advocacy

We recently explored the initial stage

of the policy development process, which involves problem identification and

issue framing, with a specific emphasis on addressing public issues related to

inequality and inequity. We will now shift our focus to the crucial stage of

agenda setting, where we identify and prioritize specific issues and problems

to be addressed by organizations and policymakers. A roadmap for moving forward

includes a quick discussion regarding stakeholders and gatekeepers in the

agenda setting process.

Stakeholders encompass individuals,

groups, organizations, and communities that have a vested interest in

government decisions and actions. This encompasses a broad range of interests,

including public policy, public administration, the allocation of resources,

and the performance of government officials, agencies, and programs. Stakeholders

play a crucial role in shaping public policy, as they can either support or

oppose decisions and activities. Their influence extends across all stages of

the policy-making process, including agenda setting. Therefore, we will be

discussing stakeholders in detail There are many different types of

stakeholders. Stakeholders involved in public policy can differ

significantly depending on the issue or problem at hand. However, some key

stakeholders that are consistently present include the government itself,

encompassing elected and appointed officials and staff across all branches of

government. Additionally,

|

| Advocacy and Policy Change Evaluation: Theory and Practice |

Gatekeepers work or function at every state of the policy-making process. Oftentimes, gatekeepers are individuals with the power to control narratives and agendas. Gatekeeping, however, sometimes happens through institutional processes or procedures that can permit, refuse, or delay opportunities to influence the policy making process. This includes such things as laws and regulations regarding lobbying, requirements for a certain number of signatures to get an issue on an agenda, or requirements that someone live in a specific area to be able to provide input or have a voice in governmental business or policy-making.

Let's consider a brief scenario to illustrate the stakeholders involved in a particular policy. New York City enacted a law in 2021, introducing new regulations within the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. These new regulations govern the application of automated employment decision tools, commonly referred to as AEDTs. Within the city of New York, employers and employment agencies are subject to new regulations that restrict the use of automated employment decision tools. These tools, which include algorithms, computational models, artificial intelligence, and screening protocols in hiring and promotion, are now prohibited. The regulation mandates that automated employment decision tools can only be utilized after a bias audit has been performed within a year of their implementation. Additionally, the results of these audits and the tools' usage must be publicly disclosed, ensuring transparency and accountability in their application. Job applicants need to be notified and they may request an alternative process. The New York City law, enacted in December 2021, initially planned for a January 2023 rollout. However, due to the overwhelming number of public comments and the need to refine the implementation guidelines, the launch was postponed until April 2023

Identifying the stakeholders involved

in this new law requires understanding the issue it aims to address. The

primary concern is that automated employment decision tools may inadvertently

introduce biases in the hiring process, potentially affecting job applicants, as you might imagine, the concern here is that

the use of these computer decision tools for the review of job applications and

resumes might actually introduce new types of bias into employment decisions. There

is a concern that human evaluators may unintentionally introduce personal

biases and prejudices when reviewing job applications and resumes, potentially

affecting the fairness of the hiring process.

Additionally, there are concerns that

these automated decision-making tools, such as algorithms and AI, may

inherently contain biases, including racial biases. This law aims to increase

transparency by making the use of these tools publicly accessible and also

mandates that those utilizing them conduct thorough assessments to identify and

address any unintentional biases or unforeseen consequences that may arise from

their application

The stakeholders involved in this

policy are diverse and numerous. Key groups include current and potential

employees, particularly those who may be vulnerable to biases in automated

hiring tools. Employers, employment agencies, and brokers are also

significantly impacted by the regulation. Data scientists who develop and

market these tools are another important stakeholder. The government, as the

policy's creator and enforcer, is naturally involved. Additionally, society at

large has a stake in the law's effectiveness, its necessity, and its overall

impact. The collective influence of stakeholders can be amplified when they

collaborate through partnerships and coalitions, sharing common values,

interests, and goals to shape the policy-making process.

The logic is straightforward.

Involving diverse stakeholders enhances consensus, streamlines processes,

boosts the chances of success, refines policy development and execution, and

enhances the credibility and backing for decisions. However, multi-stakeholder

initiatives also come with challenges, such as the financial burden of

coordinating efforts and the significant time commitment required.

Furthermore, successful

multi-stakeholder coalitions necessitate strategic process management and are

influenced by political and power dynamics. A notable example of an effective

coalition is the international joint program on the eradication of female

genital mutilation, led by UNICEF and the United Nations Population Fund. This

coalition has united stakeholders from 17 countries to implement and assess a

multi-year plan. The plan aims to modify policies and laws related to female

genital cutting, as well as empower communities to transform social and gender

norms, enhance girls and women's assets and agency, ensure access to essential

healthcare services, and contribute to a global evidence-based understanding of

the health and social harms associated with this practice.

Who are the Stakeholders of the Issue

You Care About?

To effectively advocate for a cause, consider the following steps, which can be applied across various levels, from internal organizational initiatives to local, state, federal, or international government levels. Today, we will explore the key steps involved in becoming a successful advocate:

Step 1, Identifying the issue, defining and refining

goals, understanding the process and identifying opportunities, understanding

your audience and building alliances, crafting your message, preparing written

materials, advocating, and following up. The initial step is crucial: what

specific problem do you want to address? This may involve conducting research

to become an expert and providing valuable insights to policymakers

Step 2, Clearly articulate your

objective. What specific action do you want the policymaker to take? What is

your policy objective? Are you seeking to modify an existing policy or law, or

maintain the status quo? Is there a new policy or program you wish to

establish? Are your goals short-term, intermediate, or long-term? Can you

achieve your ultimate goal through incremental steps? For instance,

anti-abortion groups successfully passed state-level laws that were later

challenged in court and eventually led to the Dobbs decision. Consider whether

your goal can be achieved through legislation, executive order, or regulation.

Alternatively, you may be educating policymakers for future action. It is

crucial to present a viable solution alongside the problem description. Think

about acceptable alternatives and compromises. Be prepared to offer compromises

on your solution if necessary. Understand the political context, including

limitations such as budget constraints or the political party in power's stance

on your request. Be as specific and detailed as possible.

Step 3, Mastering the process and identifying opportunities is crucial for achieving your policy objective. Determine the applicable process for your goal, considering whether it can be accomplished through legislative, executive, or regulatory means. Each process has distinct steps and opportunities for influence. Within the legislative process, it's essential to understand whether your solution requires authorization or appropriations. Familiarize yourself with each step, including opportunities for advocacy before the legislation is introduced, during committee hearings, bill markup, floor votes, and the conference committee process. Additionally, identify opportunities to communicate your message to decision-makers through personal relationships, in-person or virtual meetings, public hearings, briefings, town hall meetings, and other events. Effective communication can also be achieved through mail, email, grassroots efforts, print media, social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, blog posts, and campaign activities.

|

| The Power of Self-Advocacy for Gifted Learners: Teaching Four Essential Steps to Success |

Step 4, Understanding your audience and

identifying key allies is crucial when advocating for a cause. Identify the

policymakers and stakeholders who can support your goal, including

organizational leaders such as CEOs and VPs of Community Relations in the

executive branch, and legislative bodies like city councils, county

commissioners, state legislatures, and Congress. Focus on committee assignments

to pinpoint the relevant decision-makers. Research each individual to

understand their background and potential personal connections to the issue.

Schedule meetings by contacting their offices, and utilize publicly available

contact information. Additionally, consider who can effectively convey your

message and build a coalition of allies comprising interest groups, thought

leaders, and constituents. This coalition should include grassroots efforts to

amplify your message and increase its impact

Step 5, Craft a compelling message

that resonates with your decision-maker. Utilize insights gathered during

research to tailor your message to their unique interests, such as personal

connections or district-specific concerns. Different policymakers may respond

more strongly to economic or personal impact statements, so adapt your message

accordingly. Be precise and detailed in outlining the desired policy change,

including specific legislative language or actions. Prepare concise talking

points and rehearse them before meetings to ensure confidence and clarity.

Additionally, anticipate and address potential counterarguments, considering

both the substance and political contexts of the issue.

Step 6, Craft written materials that

effectively communicate your message to decision-makers. Tailor these materials

to the specific audience, as policymakers and their staff are often bombarded

with information on various topics. A concise one-page summary is an effective

advocacy tool, outlining the problem, solution, and supporting evidence.

Prepare packets of information that include relevant documents such as white

papers, press releases, policy briefs, FAQs, fact sheets, academic articles,

and other supporting materials. While hard copies can be useful, electronic

versions are often preferred. This is also an opportunity to review and refine

your talking points, incorporating additional key points as needed.

Step 7, The advocacy phase begins. To

effectively communicate your message, prioritize brevity, clarity, and

concision. Start by summarizing your key points and clearly stating what needs

to change. Maintain integrity, honesty, and respect throughout your

interactions. Respond promptly to requests for additional information and

address any questions honestly, even if you need to research the answer. Keep

in mind that policymakers and their staff are often overwhelmed and schedules

can change at short notice. Be considerate of their time constraints and be

prepared to adapt your approach as needed. Develop a concise elevator pitch to

effectively summarize your message in limited time. Building relationships and

networking are crucial aspects of advocacy. This guide outlines key principles

for effective advocacy communications, whether in-person, virtual, or written.

Always maintain a gracious demeanor and express gratitude for the time spent

with policymakers. Begin by introducing yourself, your organization or cause,

and the purpose of your visit please let me know how I may be helpful to

you or your colleagues.

Step 8, The last step is to ensure a seamless

continuation of your interactions. Always send a thoughtful note or email to

express gratitude for the meeting. Offer your support as a resource, addressing

any additional questions or concerns, and provide electronic access to relevant

information discussed during the meeting. This proactive approach fosters

ongoing communication, allowing you to maintain a strong connection and build

trust with the decision-makers.

Readings & Resources

The following article is published by McKinsey& Company on the

role of advocacy organizations in shaping public policy.

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/learning-to-navigate-the-advocacy-maze

This video provides an overview of coalition efforts to reform the NYC commercial waste system to Commercial waste. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Czj9KBov6LM

No comments:

Post a Comment